Terlingua Cemetery

Terlingua Cemetery Grave Identification Project

by

by

THE DEAD STILL SPEAK: Terlingua Cemetery

Thomas C. Alex, 2021

Thomas C. Alex, 2021

About Terlingua

The origin and derivation of the name Terlingua is obscure and lost in time. Various versions shown on old maps of the area indicate the place as Lates Lengua, Latis Lengua, Tarlinga, and Tres Lenguas, but the true origin is still debated. An alternate source comes from the various spellings of the name of an alcoholic brew made by indigenous people in the Chihuahuan Desert. The word Tesguino has been variously spelled as Teslingo and this postulation is as obscure and tenuous as the geographic place names. The name Terlingua is applied to the major tributary of the Rio Grande that flows for over eighty miles from central Brewster County to its confluence with the Rio Grande at the mouth of Santa Elena Canyon. Its waters have nourished cowboys and Indians, farmers and miners, and still support livestock and an amazing array of wildlife species.

Several small Hispanic farming settlements such as La Coyota and El Ojito appeared along the Rio Grande in the U.S. as early as the 1880s. Another small farming settlement about two miles north of the Rio Grande and located along Terlingua Creek, assumed the name Terlingua. In the late 1890s, prospectors discovered rich deposits of the mineral cinnabar in the area, and mines began to spring up to exploit the area and produce mercury, also called quicksilver. By the early 20th century, the Marfa and Mariposa, Colquitt-Tigner, Lone Star, Buena Suerte, Study Butte, and Chisos Mining Companies were busily extracting and producing quicksilver. When the Marfa and Mariposa Mining Company set up operations at California Hill around 1899, the company used the most well-known local name “Terlingua” for the post office they established, in order to transfer business correspondence. When Howard E. Perry carved his own chapter in mining history, the Terlingua post office was moved east to the Chisos mine. The local Latinos commonly referred to that place as “Chisos” because of the strong impact the mine had upon local economy and society. Under Perry’s influence, Terlingua became synonymous with the Chisos Mine. The early farming settlement became referred to as Terlingua de Abajo, or lower Terlingua.

The Mexican people who already inhabited the region found employment at the mines and played roles in the successful development of the region. Their farms and ranches provided food for the mining communities and firewood for the furnaces that turned cinnabar ore into quicksilver. These industrious people were the backbone of the mining industry and some of the families here today are descendants of the mine workers. Literally hundreds of Hispanic/Latino families contributed to the success of Terlingua as an extensive community of several thousand people.

Although much land and mining business was owned by Anglos, Hispanic/Mexicans comprised the majority of the population. The integrity and resourcefulness of these people contributed greatly to the development of Terlingua, and Hispanic culture can be seen in the architecture and felt in the attitudes of longtime residents.

The Terlingua Historic District #96000132 was listed on 10 March 1966 and is recognized for having National level of significance. Other names in this listing include Big Bend, Chisos Mining Camp, and Quicksilver Mining District. The National Archives provide information on the site at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/40971394. The areas of significance include: Community Planning and Development and Exploration/Settlement.

About the Cemetery

Texas Historical Commission (THC) recognizes the Terlingua site as a settlement and as a ghost town. The THC historic marker #6478 is located on State Highway 170, east of the road leading into the ghost town. The text states:

“Famous Texas Ghost Town Terlingua With the mother-ore cinnabar strike in 1890, Terlingua became the world's quicksilver capital, yielding 40 percent of nation's need by 1922. Its name from Terlingua (Three Tongues) Creek nearby was coined by Mexican herders. Comanche, Shawnees and Apaches lived on its upper reaches. Howard E. Perry's two-story mansion overlooked his Chisos Mining Company and townsite here, where 2,000 miners once used its jail, church, ice cream parlor, and theater. The mine flooded, mineral prices fell and Terlingua died after World War II. (1966)”

Another THC historic marker #17969 is located at the Terlingua Cemetery and recognizes one individual who is buried there, Federico Villalba. The text states:

“Villalba family tradition traces their lineage to Algiers where several generations were members of the order of Santiago. In 1764, Federico's great-grandfather, Juan Villalba, traveled to New Spain (Mexico). He founded Rancho Villalba in 1773 near present-day Aldama, Chihuahua, where Federico Villalba was born in 1858. Federico left his family's ranch and moved to San Carlos near the U.S.-Mexico border. He set up a store, selling rope, leather goods and sundries; it soon became important in San Carlos, and eventually supplied the military in the area. In the early 1880s, Villalba expanded his business interests into Texas. He settled in an area he called Cerro Villalba and opened a store. In 1889, Federico married Maria Cortez and began purchasing land. In 1902, Villalba located an outcrop of cinnabar, a mineral that produces mercury, and became the first Hispanic in the county to file a mining claim. Villalba, Tiburcio de la Rosa, D. Alarcon, and William study entered into a partnership that covered six parcels of twenty-one acres each, including what became known as the study butte mine. The Associated Mining Community took on the mine's name (Study Butte), as did Villalba's store (Study Butte Store). With a growing family, Federico built a larger house on his property along Terlingua Creek and named it Rancho Barras. Villalba amassed large tracts of land, including 15 sections in block G-4, with holdings extending from Burro Mesa to Terlingua Creek. During his life, Federico gained a reputation as a businessman and rancher, and as an advocate for Mexican Americans of the Big Bend. Villalba died of natural causes in 1933 on his ranch and is buried in Terlingua Cemetery. Federico and his legacy embody the spirit of a Texas pioneer. (2014)”

About this Mapping Project

Prior to this project, there had not been a comprehensive attempt at mapping Terlingua Cemetery. One early attempt was conducted by Janet Blair Bolton who completed a student report on her efforts. The title page of her report entitled An Overview of Terlingua, Texas: The People and Their Contribution to the “Last Frontier” indicates that it was a student project. The report does not indicate what educational institution she was associated with. A reference on the cover page indicates it was a “Senior Project, Spring Quarter, 1987” with the number SN 46357, but no other source information is indicated in the report. This report had a cover sheet from Archives of the Big Bend, Bryan Wildenthal Memorial Library, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas but the archivist there had no record of this document. This Xeroxed cover sheet had a business card from Terri D. Martinez, Reading/ESL Faculty, Reading Department, Mesa Community College, Mesa, Arizona. An attempt was made to locate a source for the report at the college library but without any successful results. The extant copy of this report was in the files of a Ms. Betina Willmon, a Terlingua High School teacher who retired in June 2021.

In addition to this report, the file contained notes made by Terlingua High School students who were assigned to use GPS to determine the geographic coordinates of the cemetery fence corners. The student notes also included oral history interview notations. Additionally, the file contained correspondence from the Terlingua Foundation regarding the listing of the cemetery with the state of Texas, Texas Historical Commission as an historic cemetery. One piece of correspondence was a letter sent from Janet Bolton to Janet Sullivan who was the chairman of the Terlingua Foundation. The letter dated February 12, 2003, indicated that Janet Blair Bolton was living in Mobile, Alabama at that time. An online attempt to locate the author indicated that Janet Blair Bolton was deceased, having passed away October 15, 2007 at the age of 73.

The Bolton report provided a brief history of the Terlingua mining community. The recording of the cemetery was indicated to be a sampling project to extract demographic information about the deceased buried in the cemetery. There was no explanation of the sampling strategy but Tables 1 and 2 listed the age and sex of several deceased individuals. There were apparently two samplings done in December and June, presumably in 1986 with the report dated Spring, 1987. A reference map of the sampling simulation listed a total of 231 graves; 45 identified by name; and 186 identified as grave, no inscription. The report provides a registry list of 73 graves, both of identified and unidentified individuals.

In 2004, students from the Terlingua School conducted a class project to begin recording the Terlingua Ghost Town Cemetery. They were instructed in use of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology and making paper records of what exists in the cemetery. This was a short term history class project that never produced a final usable product but it did instill the importance of the local history in the students, some of whom are direct descendants of the people interred here.

In 2006, Glenn Williford & Gerald Raun published their book, Cemeteries and Funerary Practices in the Big Bend of Texas, 1850 to the Present. They listed 241 individual names of people buried in a cemetery. Some of these individuals were actually buried at the “Big Bend Cemetery” also known as the Mina 248 and locally by families as Camposanto del Arroyo. Williford and Raun produced no map of graves.

There have been a few other attempts to record information about the cemetery but none have produced any available maps or documentation. A few online websites provide limited photographs and genealogical websites list the cemetery but provide little information.

This 2021 documentation is a basic inventory of individual graves and identification if any of the individual interred within. The identification is based upon the grave marker present at the date of recording. Additional information may also come from oral history interviews with people familiar with the individual interments. The initial recording involved a sequential numbering of each obvious interment as well as several possible interments based upon physical evidence of a “place marker” of stones, metal objects, etc. that serve to mark the location as an interment. Additional information on the individuals comes from genealogical research done by Robert E. Wirt prior to his death on 12 January 2013.

Robert E. Wirt has done the most extensive study of the Hispanic/Latino population of lower Big Bend. Bob served in the U.S. Navy for nine years and later worked for thirty six years with the Department of Defense working as an intelligence data analyst. After retirement in 1995, Robert served for 13 years as a volunteer historical researcher for Big Bend National Park and created an extensive genealogical database primarily on the Hispanic/Latino families of the lower Big Bend. Bob created the website Life Before the Ruins that links his historical research to living families of the Big Bend. Bob passed away 12 January 2013 but his legacy lives on.

Bob produced a spreadsheet that lists interments by name from Brewster County records and his own extensive genealogical research. His inventory contains names of 301 individuals.

He confirmed through church records as well as the physical death certificates on file with Brewster County. His spreadsheet which is posted here on Familias de Terlingua provides individual names, birth and death, date and location, as well as the cause of Death.

Some Observations

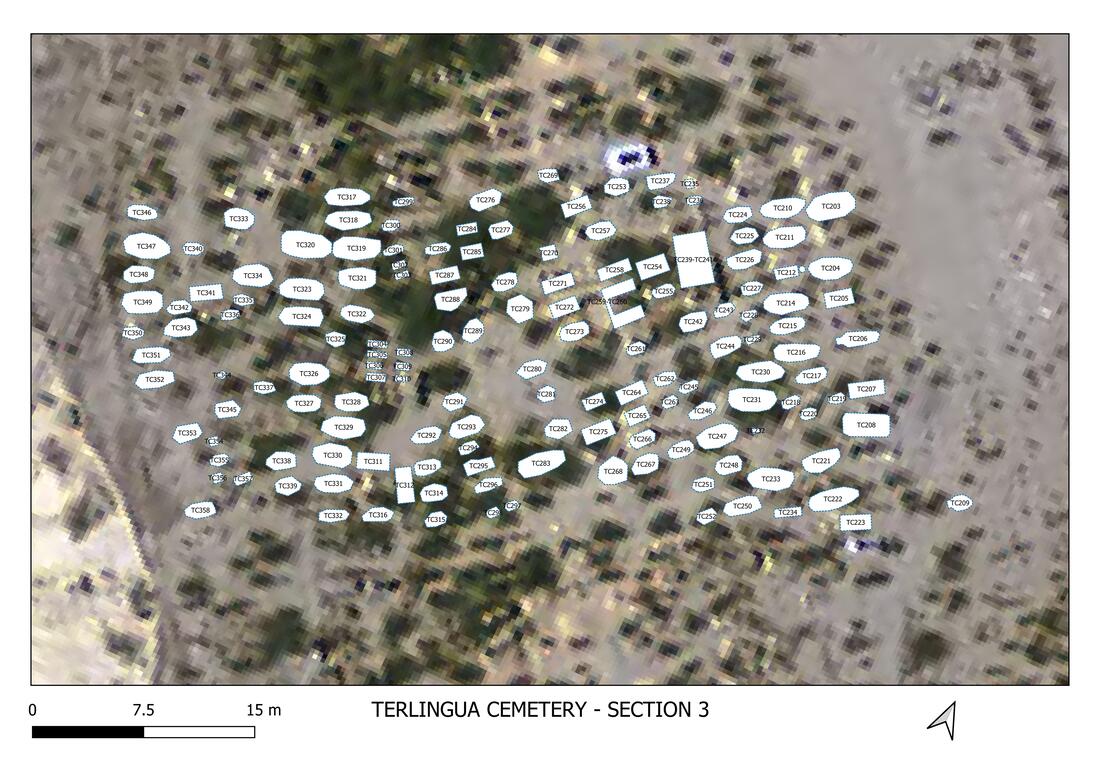

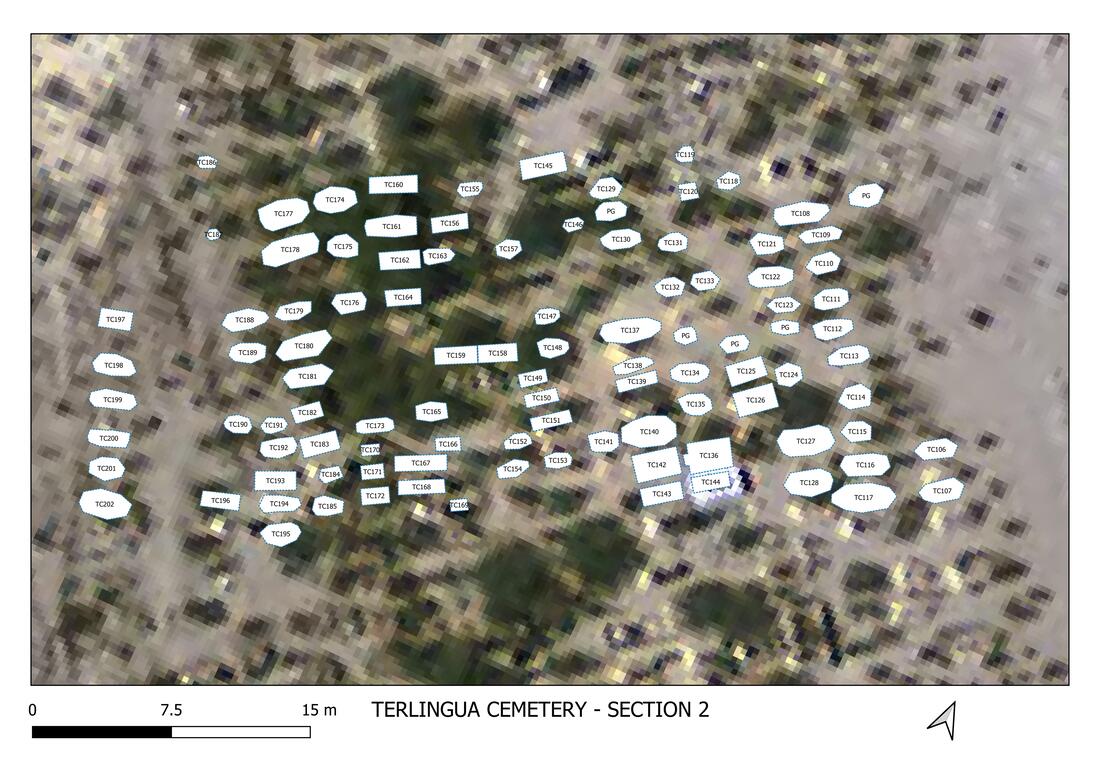

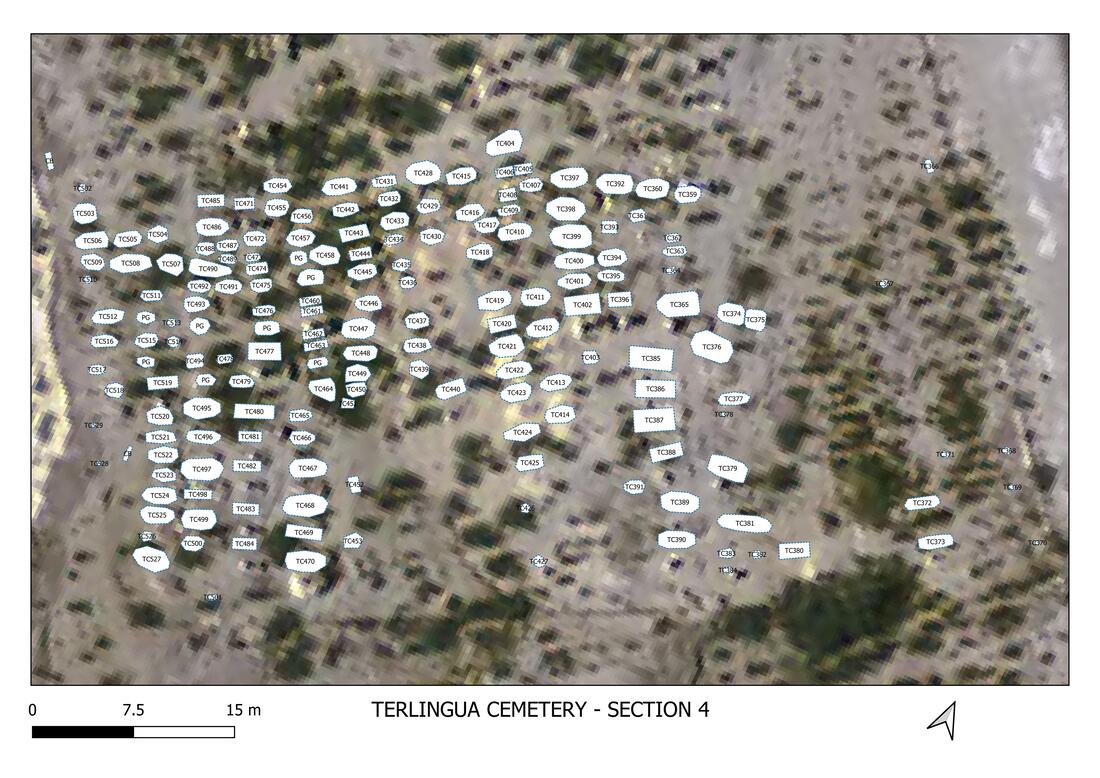

Terlingua Cemetery measures about 300 feet by about 225 feet and covers 1.44 acres. The cemetery contains 530 graves or commemorative monuments. The sheer size of the cemetery required separating it into four sections in order to map it. Section 1 begins at the northeast corner nearest the main entrance columns. Graves tend to be arranged facing eastward in rows laid north to south with subsequent rows progressing westward. Within each section, recording proceeded southward down the first row of graves then starting again at the north and recording the second row southward, and so forth across the section from east to west.

When studying the Wirt & Alex Inventory spreadsheet that is linked on this web page, several bits of information can be gleaned from the date of death and cause of death columns. The primary communicable diseases were dysentery, whooping cough, diphtheria, measles, typhus, and cholera. The major causes of death were respiratory diseases such as pneumonia, bronchial pneumonia tuberculosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, bronchitis, influenza. There is only one documented case of silicosis. These diseases would be common during this era where poor sanitary conditions existed, the lack of a community sewage system, and the hot and damp working conditions the miners found themselves in every day.

The 1918 Spanish flu epidemic was the cause of many deaths but it is poorly documented. Bob Wirt’s dataset focused solely on the Terlingua cemetery. Brewster County death records show no death certificates from 1916 to about 1925 except for two cases of in 1918 that were deaths due to gangrene and genital syphilis. There were no Spanish flu cases documented for Terlingua Cemetery. The Alpine Avalanche newspaper did not report on Spanish flu deaths especially in south Brewster County.

When looking at the graves, their construction styles and possible ages, it is difficult to determine how old any single grave may be unless there is a dated monument or dated monuments nearby. One of the oldest graves is that of Salome Ballesteros who died in 1915. Her grave is near many rock masonry grutas and rock mounds that are all unidentified. Several rock masonry grutas near Salome’s monument are multiple interments of two or more individuals so it is conceivable that these may be deaths that occurred due to the Spanish flu epidemic. The degree of deterioration of some of these monuments suggests that they are from the earlier period of interments in Terlingua Cemetery.

The Bolton report made to observation that “Vandals have desecrated every corner of the cemetery. The Chili-Cookoff which until recently was held yearly is perhaps cause of part of the destruction, but weathering and erosion have taken their toll.” (Bolton, Page 44.)

In the course of recording the existing graves, grave markers, and the identity of the deceased interred within any single grave it became apparent that the wooden “crosses” placed on many of the graves were later additions placed there by visitors to the cemetery. Even the Terlingua Foundation attempted to “repair” many of the crosses (Correspondence, Janet Sullivan to Travis Roberts, Brewster County Historical Commission, November 7, 2003). Many of the wooden “crosses” were pieces of wood taken from nearby graves, and slats removed from picket fences that were reassembled by wiring two pieces of wood into a “cross” configuration and placing them indiscriminately on various graves. Over the years, wind has blown these flimsy constructions across the cemetery and on El Dia de los Muertos, celebrants would clean up and dress up the graves, place votive candles and synthetic flowers on them, drape Mardi Gras beads and other trinkets over the crosses and leave coins and colored ornaments as offerings. In the process, wooden crosses were reset into rock mounds, set into stone cairns, and obviously relocated to other graves.

This was clearly demonstrated when a wood cross with weathered inscriptions was found at TC116 and by using photographic enhancement, the name and age of the deceased was determined to be Maria Juanita Miranda, age 7 at the age of burial. As recording proceeded across the cemetery, TC142 was recorded and it contains a newer wooden cross bearing a brass plate into which the name Juanita Miranda, birth and death dates are stamped that indicate her age of 7 years. In casual conversation with local residents who regularly participate in Dia de los Muertos, a person commented about repairing crosses, wiring pieces of wood together and placing them on graves throughout the cemetery. Some wooden crosses were moved to graves that lacked any marker. This seemingly simple act has undoubtedly confused the ability to accurately associate names with specific graves.

Foot traffic over decades of Día de los Muertos celebrations, chili cook-offs, and routine ghost town tourism has created social paths that wander between rock mounds and grutas and caused a degree of erosion. Many graves are simple earth mounds that have washed down over the past century to a low pile of rock rubble and these ephemeral graves are now part of the foot paths that crisscross and meander through the cemetery.

Today, those “bare areas” in the older parts of Terlingua Cemetery most certainly contain graves whose surface evidence has been obliterated with age. Those areas should be targeted for future research to determine whether in fact they have interments.

Thus, any particular name/grave association in this inventory must take into account the decades of human impact upon the cemetery. People are “loving” the place to death and causing irreparable harm to the historic record. The more permanent and stabile monuments and markers can be reasonably assumed to be accurate. Any wooden marker placed loosely within a rock mound can reasonably be suspect.

As one wanders through the cemetery, the ancient monuments still speak volumes that only those who take the time to listen, will hear.

The origin and derivation of the name Terlingua is obscure and lost in time. Various versions shown on old maps of the area indicate the place as Lates Lengua, Latis Lengua, Tarlinga, and Tres Lenguas, but the true origin is still debated. An alternate source comes from the various spellings of the name of an alcoholic brew made by indigenous people in the Chihuahuan Desert. The word Tesguino has been variously spelled as Teslingo and this postulation is as obscure and tenuous as the geographic place names. The name Terlingua is applied to the major tributary of the Rio Grande that flows for over eighty miles from central Brewster County to its confluence with the Rio Grande at the mouth of Santa Elena Canyon. Its waters have nourished cowboys and Indians, farmers and miners, and still support livestock and an amazing array of wildlife species.

Several small Hispanic farming settlements such as La Coyota and El Ojito appeared along the Rio Grande in the U.S. as early as the 1880s. Another small farming settlement about two miles north of the Rio Grande and located along Terlingua Creek, assumed the name Terlingua. In the late 1890s, prospectors discovered rich deposits of the mineral cinnabar in the area, and mines began to spring up to exploit the area and produce mercury, also called quicksilver. By the early 20th century, the Marfa and Mariposa, Colquitt-Tigner, Lone Star, Buena Suerte, Study Butte, and Chisos Mining Companies were busily extracting and producing quicksilver. When the Marfa and Mariposa Mining Company set up operations at California Hill around 1899, the company used the most well-known local name “Terlingua” for the post office they established, in order to transfer business correspondence. When Howard E. Perry carved his own chapter in mining history, the Terlingua post office was moved east to the Chisos mine. The local Latinos commonly referred to that place as “Chisos” because of the strong impact the mine had upon local economy and society. Under Perry’s influence, Terlingua became synonymous with the Chisos Mine. The early farming settlement became referred to as Terlingua de Abajo, or lower Terlingua.

The Mexican people who already inhabited the region found employment at the mines and played roles in the successful development of the region. Their farms and ranches provided food for the mining communities and firewood for the furnaces that turned cinnabar ore into quicksilver. These industrious people were the backbone of the mining industry and some of the families here today are descendants of the mine workers. Literally hundreds of Hispanic/Latino families contributed to the success of Terlingua as an extensive community of several thousand people.

Although much land and mining business was owned by Anglos, Hispanic/Mexicans comprised the majority of the population. The integrity and resourcefulness of these people contributed greatly to the development of Terlingua, and Hispanic culture can be seen in the architecture and felt in the attitudes of longtime residents.

The Terlingua Historic District #96000132 was listed on 10 March 1966 and is recognized for having National level of significance. Other names in this listing include Big Bend, Chisos Mining Camp, and Quicksilver Mining District. The National Archives provide information on the site at https://catalog.archives.gov/id/40971394. The areas of significance include: Community Planning and Development and Exploration/Settlement.

About the Cemetery

Texas Historical Commission (THC) recognizes the Terlingua site as a settlement and as a ghost town. The THC historic marker #6478 is located on State Highway 170, east of the road leading into the ghost town. The text states:

“Famous Texas Ghost Town Terlingua With the mother-ore cinnabar strike in 1890, Terlingua became the world's quicksilver capital, yielding 40 percent of nation's need by 1922. Its name from Terlingua (Three Tongues) Creek nearby was coined by Mexican herders. Comanche, Shawnees and Apaches lived on its upper reaches. Howard E. Perry's two-story mansion overlooked his Chisos Mining Company and townsite here, where 2,000 miners once used its jail, church, ice cream parlor, and theater. The mine flooded, mineral prices fell and Terlingua died after World War II. (1966)”

Another THC historic marker #17969 is located at the Terlingua Cemetery and recognizes one individual who is buried there, Federico Villalba. The text states:

“Villalba family tradition traces their lineage to Algiers where several generations were members of the order of Santiago. In 1764, Federico's great-grandfather, Juan Villalba, traveled to New Spain (Mexico). He founded Rancho Villalba in 1773 near present-day Aldama, Chihuahua, where Federico Villalba was born in 1858. Federico left his family's ranch and moved to San Carlos near the U.S.-Mexico border. He set up a store, selling rope, leather goods and sundries; it soon became important in San Carlos, and eventually supplied the military in the area. In the early 1880s, Villalba expanded his business interests into Texas. He settled in an area he called Cerro Villalba and opened a store. In 1889, Federico married Maria Cortez and began purchasing land. In 1902, Villalba located an outcrop of cinnabar, a mineral that produces mercury, and became the first Hispanic in the county to file a mining claim. Villalba, Tiburcio de la Rosa, D. Alarcon, and William study entered into a partnership that covered six parcels of twenty-one acres each, including what became known as the study butte mine. The Associated Mining Community took on the mine's name (Study Butte), as did Villalba's store (Study Butte Store). With a growing family, Federico built a larger house on his property along Terlingua Creek and named it Rancho Barras. Villalba amassed large tracts of land, including 15 sections in block G-4, with holdings extending from Burro Mesa to Terlingua Creek. During his life, Federico gained a reputation as a businessman and rancher, and as an advocate for Mexican Americans of the Big Bend. Villalba died of natural causes in 1933 on his ranch and is buried in Terlingua Cemetery. Federico and his legacy embody the spirit of a Texas pioneer. (2014)”

About this Mapping Project

Prior to this project, there had not been a comprehensive attempt at mapping Terlingua Cemetery. One early attempt was conducted by Janet Blair Bolton who completed a student report on her efforts. The title page of her report entitled An Overview of Terlingua, Texas: The People and Their Contribution to the “Last Frontier” indicates that it was a student project. The report does not indicate what educational institution she was associated with. A reference on the cover page indicates it was a “Senior Project, Spring Quarter, 1987” with the number SN 46357, but no other source information is indicated in the report. This report had a cover sheet from Archives of the Big Bend, Bryan Wildenthal Memorial Library, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas but the archivist there had no record of this document. This Xeroxed cover sheet had a business card from Terri D. Martinez, Reading/ESL Faculty, Reading Department, Mesa Community College, Mesa, Arizona. An attempt was made to locate a source for the report at the college library but without any successful results. The extant copy of this report was in the files of a Ms. Betina Willmon, a Terlingua High School teacher who retired in June 2021.

In addition to this report, the file contained notes made by Terlingua High School students who were assigned to use GPS to determine the geographic coordinates of the cemetery fence corners. The student notes also included oral history interview notations. Additionally, the file contained correspondence from the Terlingua Foundation regarding the listing of the cemetery with the state of Texas, Texas Historical Commission as an historic cemetery. One piece of correspondence was a letter sent from Janet Bolton to Janet Sullivan who was the chairman of the Terlingua Foundation. The letter dated February 12, 2003, indicated that Janet Blair Bolton was living in Mobile, Alabama at that time. An online attempt to locate the author indicated that Janet Blair Bolton was deceased, having passed away October 15, 2007 at the age of 73.

The Bolton report provided a brief history of the Terlingua mining community. The recording of the cemetery was indicated to be a sampling project to extract demographic information about the deceased buried in the cemetery. There was no explanation of the sampling strategy but Tables 1 and 2 listed the age and sex of several deceased individuals. There were apparently two samplings done in December and June, presumably in 1986 with the report dated Spring, 1987. A reference map of the sampling simulation listed a total of 231 graves; 45 identified by name; and 186 identified as grave, no inscription. The report provides a registry list of 73 graves, both of identified and unidentified individuals.

In 2004, students from the Terlingua School conducted a class project to begin recording the Terlingua Ghost Town Cemetery. They were instructed in use of Global Positioning System (GPS) technology and making paper records of what exists in the cemetery. This was a short term history class project that never produced a final usable product but it did instill the importance of the local history in the students, some of whom are direct descendants of the people interred here.

In 2006, Glenn Williford & Gerald Raun published their book, Cemeteries and Funerary Practices in the Big Bend of Texas, 1850 to the Present. They listed 241 individual names of people buried in a cemetery. Some of these individuals were actually buried at the “Big Bend Cemetery” also known as the Mina 248 and locally by families as Camposanto del Arroyo. Williford and Raun produced no map of graves.

There have been a few other attempts to record information about the cemetery but none have produced any available maps or documentation. A few online websites provide limited photographs and genealogical websites list the cemetery but provide little information.

This 2021 documentation is a basic inventory of individual graves and identification if any of the individual interred within. The identification is based upon the grave marker present at the date of recording. Additional information may also come from oral history interviews with people familiar with the individual interments. The initial recording involved a sequential numbering of each obvious interment as well as several possible interments based upon physical evidence of a “place marker” of stones, metal objects, etc. that serve to mark the location as an interment. Additional information on the individuals comes from genealogical research done by Robert E. Wirt prior to his death on 12 January 2013.

Robert E. Wirt has done the most extensive study of the Hispanic/Latino population of lower Big Bend. Bob served in the U.S. Navy for nine years and later worked for thirty six years with the Department of Defense working as an intelligence data analyst. After retirement in 1995, Robert served for 13 years as a volunteer historical researcher for Big Bend National Park and created an extensive genealogical database primarily on the Hispanic/Latino families of the lower Big Bend. Bob created the website Life Before the Ruins that links his historical research to living families of the Big Bend. Bob passed away 12 January 2013 but his legacy lives on.

Bob produced a spreadsheet that lists interments by name from Brewster County records and his own extensive genealogical research. His inventory contains names of 301 individuals.

He confirmed through church records as well as the physical death certificates on file with Brewster County. His spreadsheet which is posted here on Familias de Terlingua provides individual names, birth and death, date and location, as well as the cause of Death.

Some Observations

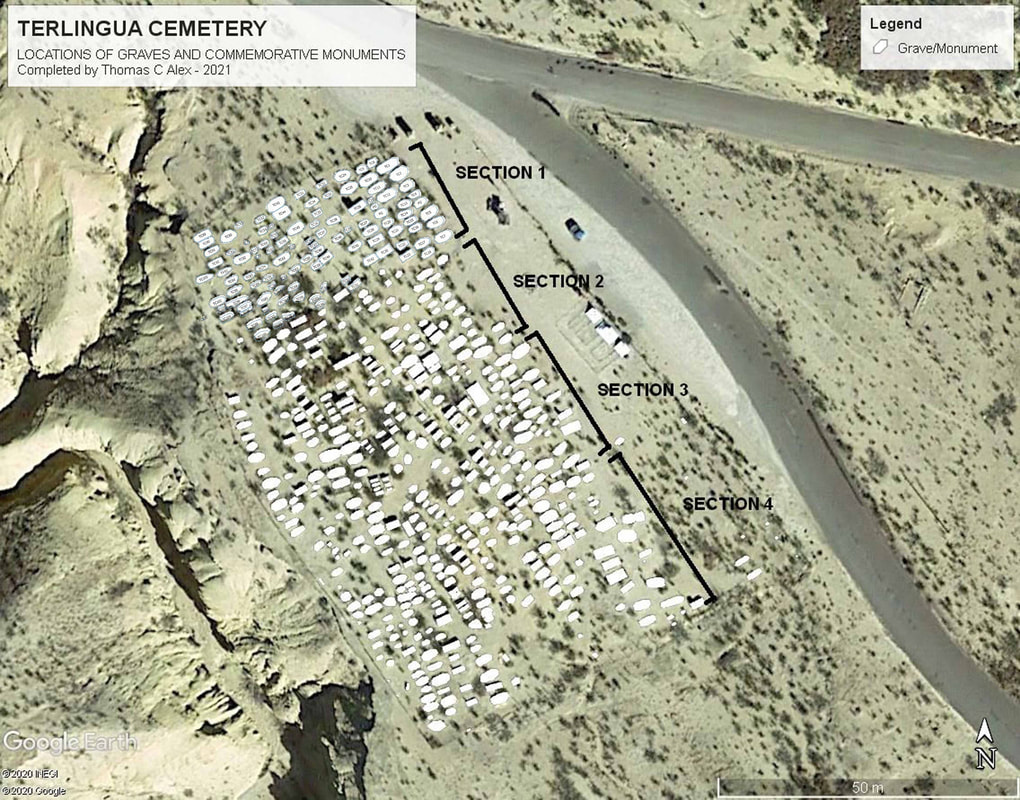

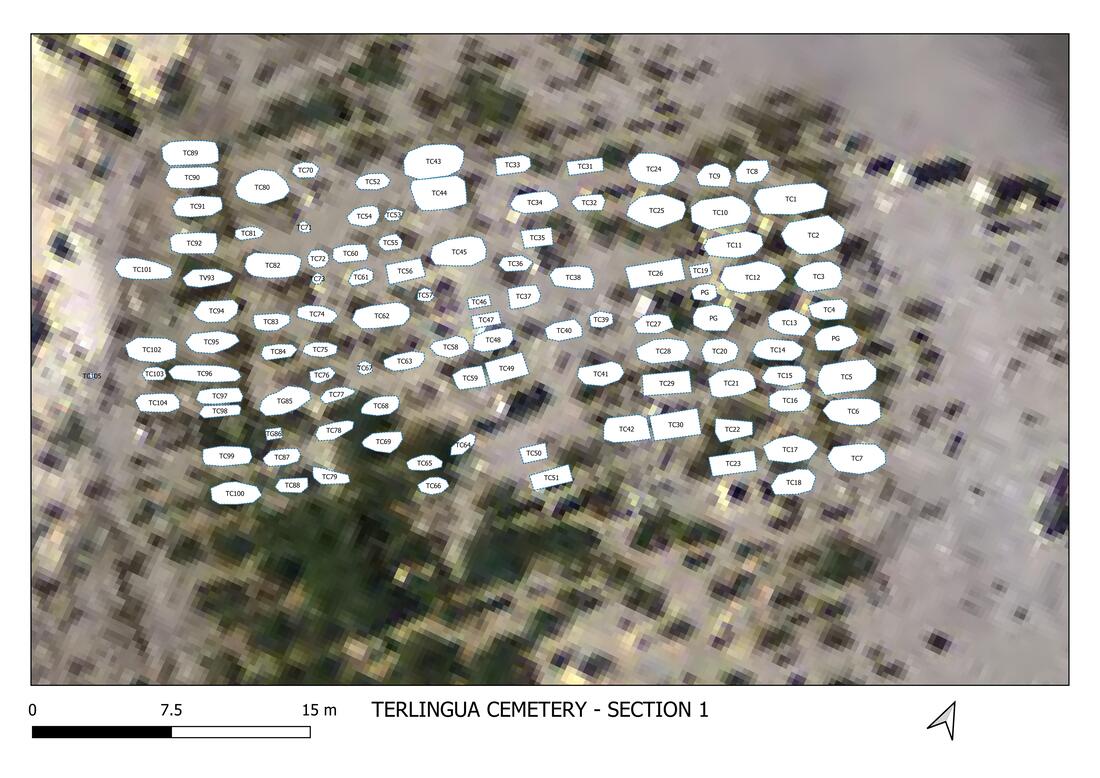

Terlingua Cemetery measures about 300 feet by about 225 feet and covers 1.44 acres. The cemetery contains 530 graves or commemorative monuments. The sheer size of the cemetery required separating it into four sections in order to map it. Section 1 begins at the northeast corner nearest the main entrance columns. Graves tend to be arranged facing eastward in rows laid north to south with subsequent rows progressing westward. Within each section, recording proceeded southward down the first row of graves then starting again at the north and recording the second row southward, and so forth across the section from east to west.

When studying the Wirt & Alex Inventory spreadsheet that is linked on this web page, several bits of information can be gleaned from the date of death and cause of death columns. The primary communicable diseases were dysentery, whooping cough, diphtheria, measles, typhus, and cholera. The major causes of death were respiratory diseases such as pneumonia, bronchial pneumonia tuberculosis, pulmonary tuberculosis, bronchitis, influenza. There is only one documented case of silicosis. These diseases would be common during this era where poor sanitary conditions existed, the lack of a community sewage system, and the hot and damp working conditions the miners found themselves in every day.

The 1918 Spanish flu epidemic was the cause of many deaths but it is poorly documented. Bob Wirt’s dataset focused solely on the Terlingua cemetery. Brewster County death records show no death certificates from 1916 to about 1925 except for two cases of in 1918 that were deaths due to gangrene and genital syphilis. There were no Spanish flu cases documented for Terlingua Cemetery. The Alpine Avalanche newspaper did not report on Spanish flu deaths especially in south Brewster County.

When looking at the graves, their construction styles and possible ages, it is difficult to determine how old any single grave may be unless there is a dated monument or dated monuments nearby. One of the oldest graves is that of Salome Ballesteros who died in 1915. Her grave is near many rock masonry grutas and rock mounds that are all unidentified. Several rock masonry grutas near Salome’s monument are multiple interments of two or more individuals so it is conceivable that these may be deaths that occurred due to the Spanish flu epidemic. The degree of deterioration of some of these monuments suggests that they are from the earlier period of interments in Terlingua Cemetery.

The Bolton report made to observation that “Vandals have desecrated every corner of the cemetery. The Chili-Cookoff which until recently was held yearly is perhaps cause of part of the destruction, but weathering and erosion have taken their toll.” (Bolton, Page 44.)

In the course of recording the existing graves, grave markers, and the identity of the deceased interred within any single grave it became apparent that the wooden “crosses” placed on many of the graves were later additions placed there by visitors to the cemetery. Even the Terlingua Foundation attempted to “repair” many of the crosses (Correspondence, Janet Sullivan to Travis Roberts, Brewster County Historical Commission, November 7, 2003). Many of the wooden “crosses” were pieces of wood taken from nearby graves, and slats removed from picket fences that were reassembled by wiring two pieces of wood into a “cross” configuration and placing them indiscriminately on various graves. Over the years, wind has blown these flimsy constructions across the cemetery and on El Dia de los Muertos, celebrants would clean up and dress up the graves, place votive candles and synthetic flowers on them, drape Mardi Gras beads and other trinkets over the crosses and leave coins and colored ornaments as offerings. In the process, wooden crosses were reset into rock mounds, set into stone cairns, and obviously relocated to other graves.

This was clearly demonstrated when a wood cross with weathered inscriptions was found at TC116 and by using photographic enhancement, the name and age of the deceased was determined to be Maria Juanita Miranda, age 7 at the age of burial. As recording proceeded across the cemetery, TC142 was recorded and it contains a newer wooden cross bearing a brass plate into which the name Juanita Miranda, birth and death dates are stamped that indicate her age of 7 years. In casual conversation with local residents who regularly participate in Dia de los Muertos, a person commented about repairing crosses, wiring pieces of wood together and placing them on graves throughout the cemetery. Some wooden crosses were moved to graves that lacked any marker. This seemingly simple act has undoubtedly confused the ability to accurately associate names with specific graves.

Foot traffic over decades of Día de los Muertos celebrations, chili cook-offs, and routine ghost town tourism has created social paths that wander between rock mounds and grutas and caused a degree of erosion. Many graves are simple earth mounds that have washed down over the past century to a low pile of rock rubble and these ephemeral graves are now part of the foot paths that crisscross and meander through the cemetery.

Today, those “bare areas” in the older parts of Terlingua Cemetery most certainly contain graves whose surface evidence has been obliterated with age. Those areas should be targeted for future research to determine whether in fact they have interments.

Thus, any particular name/grave association in this inventory must take into account the decades of human impact upon the cemetery. People are “loving” the place to death and causing irreparable harm to the historic record. The more permanent and stabile monuments and markers can be reasonably assumed to be accurate. Any wooden marker placed loosely within a rock mound can reasonably be suspect.

As one wanders through the cemetery, the ancient monuments still speak volumes that only those who take the time to listen, will hear.

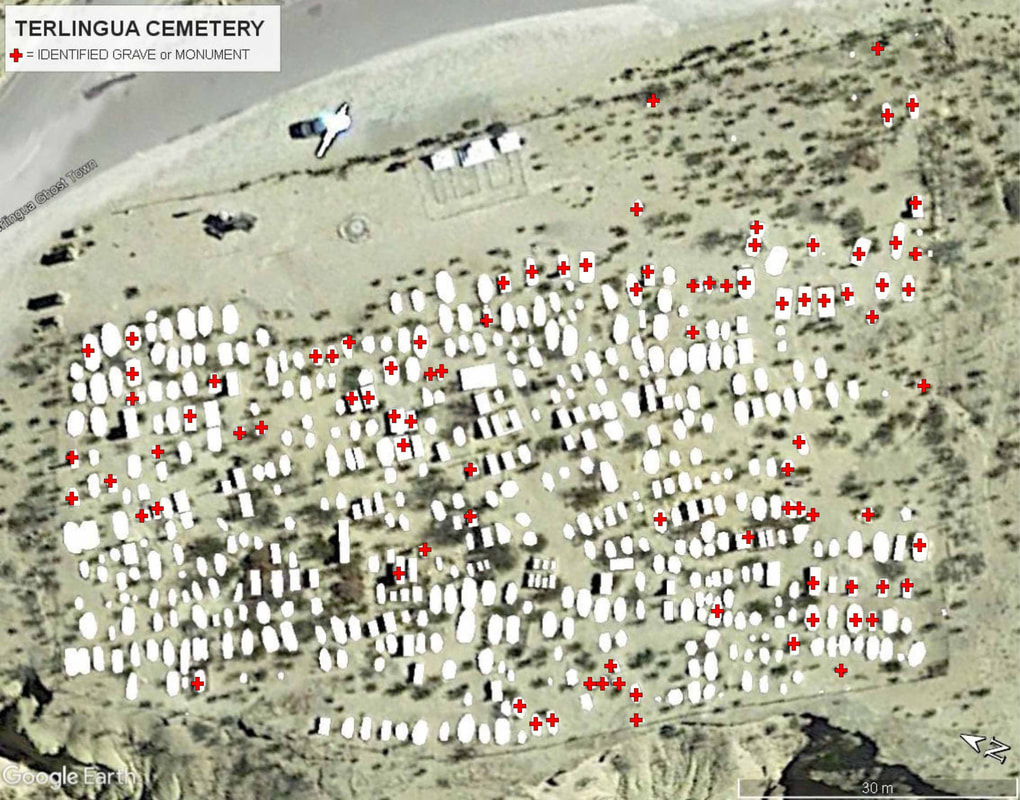

Thomas C. Alex collected identifying information for many of the grave sites at the Terlingua Cemetery. In the map above he has placed a red cross over grave sites that he has identified. He then created an interactive Google Earth map of the cemetery which displays known details for each grave site.

To see his work

To see his work

- Click here to download Tom's cemetery map file for Google Earth: terlingua_cemetery_1-24-2021.kmz.

- Click on the map file you downloaded to open it in Google Earth. You may need to download Google Earth to your computer in order to see this.

- Click on an individual image of the grave to see its information.

Bob Wirt and Tom Alex have produced a spreadsheet of the information for the people buried in the Terlingua Cemetery.

Click here to download it.

Click here to download it.

If you wish to submit information or images relevant to the Terlingua Cemetery

you can use the form below.

you can use the form below.

This page created October 2021 by

Thomas C. Alex, consulting archeologist

G4 Heritage Consulting

PO Box 40, Terlingua, TX 79852

432-371-2917 (Land) ^ 432-294-5550 (Cell)

Thomas C. Alex, consulting archeologist

G4 Heritage Consulting

PO Box 40, Terlingua, TX 79852

432-371-2917 (Land) ^ 432-294-5550 (Cell)